- HOME

- ABOUT

- BIOS

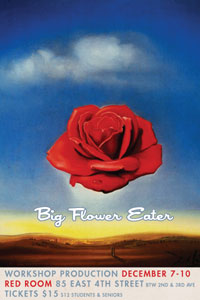

Horse Trade Theater Group in association with Direct Arts present a workshop production of BIG FLOWER EATER, a new play devised by Victoria Linchong, with assistance from Kim Chinh and Helen Kim. Exploring shamanism in three unique Asian cultures (Hmong, Korean and Taiwanese), BIG FLOWER EATER uniquely blends traditional Asian rituals with carnival illusions, reflecting Linchong’s background as a Taiwanese-American and a former performer at the Coney Island Sideshow. In BIG FLOWER EATER, a young Taiwanese woman pastes her grandmother’s fortunes on her bathroom wall, setting off a host of otherworldly activity in her small Lower East Side lavatory. The ghost of her eccentric grandmother takes up residence in the ceiling causing a constant leak, while the lost soul of an epileptic Hmong girl finds comfort in the cool porcelain of the tub, which she often clogs. The mysterious malfunctions of the bathroom are finally explained with a visit from a Korean friend, whose disturbing receptivity to the spirits leads to a revelation regarding the long tradition of shamanism in her now-Christian family. |

Victoria Linchong is a Taiwanese-American actress, writer, producer and director working in both theater and film. As an actress, she most notably had a feature role in the Obie Award play HOT KEYS (Naked Angels). Her producing credits include five plays by James Purdy, including SUN OF THE SLEEPLESS with Laurence Fishburne, and the Obie Award winning anti-war event STOP THE WAR: A FESTIVAL FOR PEACE IN THE MIDDLE EAST. More recently, Victoria produced, directed and acted in PAPER ANGELS by Genny Lim, which workshopped in New York City and traveled to San Francisco, where it played to capacity crowds outdoors in Chinatown and won Best of the San Francisco Fringe. She is currently in post-production on ALMOST HOME: TAIWAN, a documentary on Taiwan’s identity and independence. Victoria studied acting with the legendary Sanford Meisner and at the British American Drama Academy at Oxford University in England. She was Development Assistant at Film Forum and is currently Grants Manager at Theatre for a New Audience. |